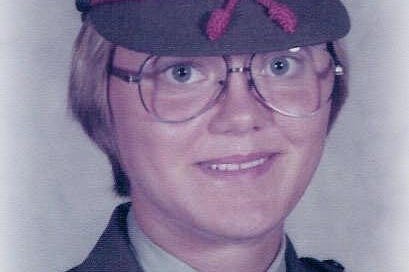

The 2024 Women Marines Convention kicks off today in Atlanta, Georgia. Today’s female Marine recruits train the same as male Marines. That wasn’t the case in the 1970s. Here’s my Marine origin story, a chapter from my forthcoming memoir.

When I moved to Montana in 1975, I transferred my Army Reserve obligation to a Montana engineering post. Because they didn’t have medical typists, they reclassified me as a clerk typist. They ignored me and there wasn’t much to do on the monthly drill weekends.

One month a flyer announcing the admission of women into West Point Military Academy caught my eye. How cool would it be to be in the first class of women cadets?

I carefully crafted my letter of application, explaining my reserve military service, my Non-Commissioned Officer Academy completion, and closed by saying it would be an honor to be in the first West Point class with females.

The rejection letter I received said since I hadn’t taken college prep courses in high school, I’d have to attend a year of college prep. I missed the 21-year-old age cut-off by one stinking year. I felt sentenced to being a secretary for the rest of my life.

Growing up I had always admired the “wall of honor” my Little Grandma and Grandpa had in their guest room. Pictures of my four handsome uncles in their military uniforms had inspired me to think about military service so I had joined the Army Reserve. I’d often threaten my dad I’d go active duty. After a while, he quit believing I would.

When I heard my reserve unit’s annual two-week training would be in the Mojave Desert, I was not thrilled. With the desert looming and the rinse and repeat routine of my job, I was done…done sitting behind a desk and done with being a secretary. I wanted to kick ass and take names.

First, I went to see the Army recruiter. Their door was locked. Next, I tried the Air Force recruiter, but their door was locked too. On the way out the door, I saw the only on-duty recruiter in the office was from the Marine Corps. I looked up at the poster of the proud Marine, turned the knob, and asked, “Does the Marine Corps have women?”

The fit Marine recruiter stood and his face looked bemused, as if everyone should know the answer. “Of course we do.”

“Where do I sign up?” If he had a quota, I’d just made his job easy.

“Does my Army Reserve bootcamp count?”

“No,” the Marine recruiter said. “Anyone who joins the Marine Corps, whether they come in off the street or have been in the military before, has to go to Marine Corps bootcamp.”

I wasn’t dissuaded. I was ready. My rank would be reduced to a Marine Corps Recruit Private, three rungs lower than I had been in the Army Reserves.

I signed all the papers and showed him my Army Reserve ID card.

“It won’t be a problem. You’ll need to take a physical and a test.”

“No problem,” my voice sounding more confident than I felt knowing the reputation of Marines. But if there was anywhere where I would be able to kick ass and take names, it was the Marine Corps. Plus, I reasoned, being in the Marines would kill me or cure me of my fear of becoming my mom.

Marine recruits from around the country are booked on late flights so they arrive at bootcamp in the dark for maximum disorientation. After landing in Savannah Georgia, male and female recruits board a bus headed to Parris Island, South Carolina, the East Coast Marine recruit training facility and the only one to train women in the 1970s. As the Marine guard waved the bus through the Parris Island gates, I knew my life would forever be changed.

When the bus pulled up in front of a building, fit Marines in Smokey the Bear hats charged onto the bus screaming.

“Boys. Get out. Now! Girls, lock your eyes, front and center.”

The boys scrambled over each other to get off the bus. Without turning my head, my eyeballs glanced to my right and saw the yellow footprints the smokies were yelling about. Painted on the street were sixty pairs of yellow footprints, heels together, toes at a 45-degree angle, in four straight rows of 15 pairs. The boys stumbled over each other to find an empty pair to stand on. I saw the edge of a Smokie hat touch a boy’s face and I freaked out a little seeing how close he came. If his smokie hat hadn’t been there, I swear their noses would have touched.

I sensed a lot of girls around me thinking the same thing I was, what the heck did I get myself into? Maybe I can still go home. As if reading our minds, one of the stern Marines said, “You’re not going home, you’re getting off at the next stop. Sit up straight. Eyes front. Ears open.”

The bus slowly pulled forward and rounded a corner. We were barely breathing, worried about our fates. After a couple of blocks, the air brake squealed, the bus pulled to a stop, the doors open, and onto the bus rushed female Marines with the same bark in their voice.

“Get off my bus! What are you doing on my bus? Get out of your seats and get out now.”

Girls were scurrying to gather their wits and courage to hustle off the bus. The female Marines sounded as scary as the male Marines though they didn’t wear the smokie hats. I lined up as best as I could in the dark.

The Army Reserve had taught me how to stand at attention so while the barking Marines yelled at girls around me about “Get your eyes off me recruit” and “Stand up straight,” and “Look straight ahead,” I already had that nailed.

I also knew I needed to keep a low profile, do as I was told, and keep my head down. The last thing you wanted was to call attention to yourself because not only would you be singled out, but the whole group might be punished because of your misbehavior.

“Listen up recruits, you’re in my Marine Corps now. You will do what you’re told, when you’re told. Do you understand recruits?!”

“Yes.”

“You will answer ‘Ma’am, yes Ma’am” when I ask a question. Do you understand?”

“Ma’am, yes Ma’am.”

“I…can’t…hear…you!”

“Ma’am, yes Ma’am!” I felt like I was screaming at the top of my lungs. We all were. We were never to address the DIs using first person, we were to address ourselves in third person. Bootcamp is about working together as a team and not as an individual.

The rest of in-processing was an exhausting blur.

Eventually all the recruits were assigned to either platoon 6A or 6B. We shuffled into a large, stark squad bay with the distinct scent of Pine-Sol disinfectant. The thirty sets of bunkbeds with green wool blankets and wooden footlockers for our possessions awaited our arrival. We could finally crash after the long confusing night.

Over the next couple of days, we met our DIs and unsmiling Marines and civilians issued us the clothing we would wear during bootcamp: light blue short-sleeved blouses, navy blue pants, a small navy-blue hat they called a cover, and black leather shoes along with a powder blue physical training or PT uniform and sneakers. All the blue clothing was confusing to me because we hadn’t joined the Navy, and the baggy culotte PT uniform was like something from the 1940s.

Bootcamp settled into a routine: rise and shine at 0600 for physical fitness or PT; breakfast; class work; and training, lots of training. We learned how to survive the gas chamber, we learned the Marine General Orders and were expected to recite them on command. We learned about the Marine Corps’ storied history from its 1776 founding in a Philadelphia tavern to the historic Iwo Jima battle, through the Vietnam years.

Turns out the Marine Corps is under the Department of Navy because Marines served on naval ships. Maybe that explained our weird blue clothing and all the names they told us to call things: racks instead of bunks, cover instead of hat, head instead of bathroom, and bulkhead instead of wall.

There were a couple of big differences from my Army basic training. We were taught to serve tea in the event we would be assigned as staff to a General officer. Most surprising, we received make-up classes. When we were in our dress uniforms, we were required to wear four articles of make up: eye shadow, mascara, blush, and lipstick to match the scarlet cap cord of our dress cover. Another bizarre uniform requirement was wearing a girdle. It did not matter how thin a recruit was, girdles were required during inspections. Everyone ditched them after boot camp.

We spent long hours learning to march together as a unified platoon on the asphalt parade deck. Band and Army training had developed my love of marching as a group, but as a Marine recruit, my heart swelled with pride and a sense of belonging when marching with my platoon.

When I enlisted, I thought it would be patriotic and special to be in the Marine Corps during the nation’s 200th birthday on July 4th, 1976. It was no doubt a special day for everyone else in the nation but for us recruits, it was “field day” or cleaning the barracks. We polished the floors with a beastly buffer machine, we tended the gardens outside, and performed all the other chores assigned by our DIs to keep us busy.

The girls in my platoon were a huge cross-section from all corners of America. Some were fresh out of high school and many, like me, were in our twenties. One woman had her bachelor’s degree, and I was mystified why she enlisted instead of going straight to Officer Candidate School. She told us she wanted to start as an enlisted Marine for the experience, then go to OCS.

After a long day of PT, marching, and sitting in classes, dinner time was a welcome respite. Male recruits served us and kept their eyes on what they were doing. Some females tried to get the attention of those shaved headed male recruits, many of them wearing the black Marine Corps issued “birth control” spectacles. With their DIs watching, they didn’t dare.

The chow hall was not a place for idle conversation. Eating was serious business. The DIs kept a close eye on us recruits as we went through the chow line. If they saw a recruit who was close to their weight limit take a dessert, they would take the dessert off their plates at the end of the line.

Once when eating chow, I sat across from a sad-eyed recruit who was terribly homesick for her husband and two small children. I wondered what made her think joining the Marine Corps was a good idea, but I never asked. That night, tears were streaming down her face, dripping onto her plate, and making a teary mashed potato puddle. I couldn’t imagine how it must have felt to leave your family only to go through the hell we experienced daily.

She had been assigned to Casual Platoon, a kind of Marine Corps purgatory where the injured or those who couldn’t meet the training requirements were placed. Once assigned, recruits stayed an indefinite time until the leadership of recruit training figured out what to do with you. I felt sorry for her and wondered how long it would take before they would let her go back home to her family.

Sunday was our only day of rest. Recruits were also allowed to practice their respective faiths. Although I considered myself a lapsed Lutheran, I saw it as a chance to get out of the barracks, so I volunteered at the Lutheran church, a welcome break from the routine. The rest of the day, we did our laundry and ironing for the week, wrote letters, and enjoyed some rare downtime.

One Sunday afternoon, a runner announced to the squad bay, “Private Sinness, report to the DI hut.”

Panicked, I wondered what I had done. It was never good when the DIs called you out. I quickly reviewed the last week in my mind, and nothing came up. I hustled to the DI hut door where the stern face of our Senior Drill Instructor Gunnery Sergeant Simmons was awaiting my arrival.

As I approached the doorway, I felt like throwing up, but I automatically locked my heels together with my toes pointed out at 45 degrees, arms at my side with fingers curled toward at the sides of my legs, eyes staring straight ahead.

“Ma’am, Private Sinness reporting as ordered Ma’am.”

“Private Sinness,” Gunny Simmons said. After a long pause, she continued, “What is this?” She was holding my Army Reserve identification card.

Shit, there it is. When I left Billings, neither the Army Reserves nor the Marine recruiter had asked me for it. Since I didn’t know what to do with the ID card, I carried it in my pocket. I must have missed it when I did laundry.

“Ma’am, this recruit was in the Army Reserves and when this recruit joined the Marine Corps, no one asked her for it, so she didn’t know what to do with it, Ma’am!”

“Are you telling me the truth Private?”

“Ma’am, yes Ma’am.”

“You know we’ll check it out, don’t you?”

“Ma’am, yes Ma’am.”

“OK Private, you’re dismissed.”

I put my right toe behind and to the left of my left heel and turned to do about face to my right as smartly as I could. I felt relieved…and Gunny Simmons never mentioned it again.

When I was told I was going to be promoted to Private First Class a few days before graduation, I was elated. I might have had a head start on gaining rank had I gone active-duty Army since I had been an E-4 in the Reserves, but there was synchronicity in having had only the Marine recruiter on duty on my ‘done with being a secretary’ day. The Marine Corps gave me the sense of belonging I had unknowingly been seeking.

When I received the eagle, globe, and anchor Marine insignia, I knew I had earned it. From that moment on, it felt emblazoned on my heart and a part of my identity.

I was disappointed my dad couldn’t be there to witness me becoming a Marine when I stood in front of my platoon as one of the three meritoriously promoted recruits. Even if he’s not here, I’m proud of myself. I’ll remember this feeling when I have a down day.

I was now a Marine.

Stay tuned for more Dispatches from the Semper Fi Sisterhood, the biennial Women Marines Convention.

The Marines didn't let you stagnate in the steno pool!

This made me smile, Deb, and feel very proud of you! I love that you wanted to kick ass and take names. It was your inner Marine coming out! The photos are great - I can't wait to read more!